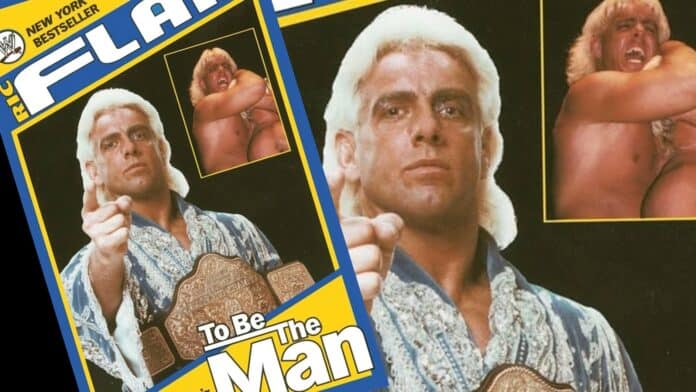

In the grandiose, often hyperbolic world of professional wrestling, few figures loom as large as “The Nature Boy” Ric Flair. His autobiography, “To Be the Man,” co-written with Keith Elliot Greenberg and edited by Mark Madden, serves as a testament not only to his longevity inside the squared circle but to a lifestyle of excess that borders on the mythical. Published by World Wrestling Entertainment (WWE) in 2004, the book peels back the sequined robes to reveal the man behind the “Woooo!”—a man fueled by insecurity, immense talent, and an unquenchable thirst for the spotlight.

Flair’s story begins with a revelation that sets the tone for a life of unpredictability. Born in Memphis in 1949, Flair was one of the thousands of children victimized by the infamous Georgia Tann and the Tennessee Children’s Home Society black market adoption ring. “My mother probably thought I was stillborn,” Flair writes. “That’s what they told a lot of the girls whose kids ended up with the Tennessee Children’s Home Society in Memphis—their babies were dead, and they just needed to sign a couple of papers.” He cites the official agency report regarding his biological parents: “Olive Phillips and Luther Phillips did abandon and desert said child.” Adopted by Richard and Kathleen Fliehr, he was raised in Edina, Minnesota, far removed from the southern territories he would one day rule.

Surviving the Ice: Training with Verne Gagne

Flair’s entry into professional wrestling was a trial by freezing fire. After dropping out of college and working as a bouncer, he caught the eye of Olympic weightlifter Ken Patera, who introduced him to the legendary promoter Verne Gagne. Gagne’s training camp in Minneapolis was notoriously brutal, designed to weed out anyone lacking genuine toughness. Flair describes the conditions vividly: “We’d start off running along this frozen creek, slipping and sliding. I’m not exaggerating—you’d have to wear three sweatsuits. The only way to stay warm was to keep moving and not slow down—the whole day, for six or eight hours.”

The physical toll was exacerbated by the sadistic tendencies of the trainers, particularly Billy Robinson. Flair recounts a harrowing incident involving his fellow trainee, Hossein Khosrow Vaziri (The Iron Sheik). After Khosrow bragged about his amateur wrestling background, Robinson decided to teach him a lesson in the “hooker” style of submission wrestling. Flair writes, “Robinson was an expert on ‘hook’ style, which was illegal in the amateur ranks, and after about ten minutes, he brought the point of his knee down into Khosrow’s thigh, fucking up his hip. Khosrow was in agony as Robinson turned him over and pinned him.”

The brutality drove Flair to quit just days into the camp. However, Gagne refused to let him go. “Verne came over to my house, grabbed me by the shirt and threw me out on the front lawn,” Flair recalls. Gagne screamed at him, “It took you five years to graduate high school. You quit college. Well, you’re not quitting this. I didn’t sign you up to be a quitter.” Flair returned, driven by a desire to prove he was better than Gagne thought.

The Plane Crash that Created the Nature Boy

The defining moment of Flair’s early career—and perhaps his life—occurred on October 4, 1975. While flying a Cessna 310 to a show in Wilmington, North Carolina, the pilot, Mike Farkas, realized he had dumped fuel to lighten the load and miscalculated. Flair describes the terrifying moments before impact: “Valentine pointed at the gas gauges and started laughing. ‘Heh-heh-heh, we’re out of fuel.’… We had just crossed the Cape Fear River when the right engine died. I was thinking, God, when are we going to activate the reserve tanks? Then I heard a boom, and it scared the shit out of me.”

The plane crashed short of the runway, breaking Flair’s back in three places. “I blacked out again, and when I came to, I was on one of those old steel X-ray tables,” Flair writes. Despite doctors telling him his career might be over, Flair’s resolve was absolute. “Some doctors, including my own father, believed that I would never be able to perform at a high level in the ring with the injuries I’d endured… But, hell, I was twenty-four years old; I couldn’t wait that long! I loved wrestling and everything about it, and I believed with all my heart that I would recover sooner. I just wouldn’t be denied.”

The crash forced Flair to alter his wrestling style from a power-based brawler to a technical craftsman who relied on psychology and bumping. It was during his recovery that the “Nature Boy” persona was born, inspired by the original Nature Boy, Buddy Rogers. “George Scott is the one who came up with the idea of naming me Nature Boy,” Flair explains. “I knew that Rogers used to strut in the ring, so I started doing the same thing. That doesn’t mean that I did the same strut… I just developed a ‘Ric Flair strut,’ sometimes breaking into it in the middle of the action.”

The NWA World Champion: Sixty-Minute Man

Flair’s ascent to the NWA World Heavyweight Championship marked the beginning of his “60-minute man” legend. As the touring champion, his job was to visit different territories and make the local hero look like a million dollars. He took immense pride in his stamina and his ability to work with anyone. “I’m the kind of guy you could put the whole world around, and I can support every part of it,” Flair bragged in promos. “I’m not a movie actor—better looking than most of them. I’m not a rock star, but I can dance and sing my fanny off. I just happen to be a kiss-stealing, wheeling, dealing, limousine-riding, jet-flying son-of-a-gun that you know to be—Woooo!—the World’s Heavyweight Wrestling Champ.”

The book is replete with stories of the chaos that ensued in foreign territories, particularly the Dominican Republic. Flair details a match against local hero Jack Veneno where the crowd was so hostile that he was forced to throw the match to save his life. “The crowd was screaming, cursing the United States… It was absolutely fuckin’ crazy,” Flair writes. When Roddy Piper, who accompanied him, tripped Veneno, soldiers pointed rifles at Piper’s head. Flair realized the danger: “This was the spot where I was supposed to cover Veneno and steal the win, but I got so scared that I pulled him on top of me and yelled, ‘Pin me!’… Then I looked at the referee. ‘Count!’ I screamed.” Flair left the belt in the Dominican Republic and fled the country, noting, “I’d rather leave alive.”

The Four Horsemen and the Lifestyle

Perhaps the most celebrated era of Flair’s career involves the Four Horsemen—a stable consisting of Flair, Arn Anderson, Tully Blanchard, and Ole Anderson (later replaced by Lex Luger and Barry Windham), managed by J.J. Dillon. They were not just a gimmick; they were a lifestyle. Flair writes, “We bought five Mercedes. We’d pull them up on the ramp at Butler Aviation in Charlotte, the pilots would get our bags, and we’d walk up to one of Jim Crockett’s private planes and fly out. When we landed, a limo would pick us up at the airport. We’d check into the hotel, go to the gym, go to work, kick some ass, head back to the limo, and party.”

The bond between the Horsemen was real, particularly between Flair and Arn Anderson. “Arn became as big a part of my life as the General, my high-school buddy… There was no jealousy in the Four Horsemen. Everybody liked the idea and ran with it,” Flair states. The group lived the gimmick to the hilt. Flair estimates his personal expenses were astronomical: “When the Horsemen were running heavy, I ran up an annual bill of $60,000 for limousines alone.”

The partying stories are legendary. Flair recounts a night called “The Great Shootout” at his house, pitting Roddy Piper against “The Purple Haze” Mark Lewin to see who could drink the most. “In the course of the night, I poured Piper and Lewin each about thirty shots of Crown Royal,” Flair writes. “The nod goes to the Hot Rod. Around six-thirty in the morning, I sent everyone out. Piper walked upstairs into my guest room, lay down, and went to sleep. Lewin was carried from the house.”

Jim Herd and the “Spartacus” Debacle

As the 1990s approached, the NWA morphed into WCW (World Championship Wrestling) under the ownership of Ted Turner. The arrival of corporate executive Jim Herd marked a low point in Flair’s career. Herd, a former Pizza Hut manager, did not understand wrestling or Flair’s value. “Jim Herd was an idiot,” Flair states bluntly. “This is not defamation. I’m just telling you history. The man had no right to be anywhere near a wrestling company.”

Herd notoriously tried to repackage Flair, believing the “Nature Boy” persona was dated. Kevin Sullivan recounts the meeting in the book: “Because Ric had been around for so long, Herd thought that his image needed updating—from the Nature Boy to a Roman gladiator. He said, ‘Let’s cut Ric’s hair, put an earring in his ear, and give him a shield. We’ll call him Spartacus.’ He actually wanted to change Ric Flair’s name!”

The tension culminated in Herd firing Flair in 1991 over a contract dispute. Flair, still the champion, took the “Big Gold Belt” with him because he had never been refunded his $25,000 deposit on the title. “I sent the championship belt to Vince McMahon the next day,” Flair writes. This led to the surreal sight of Bobby Heenan displaying the NWA World Title on WWF television, proclaiming, “Comparing this belt to Hulk Hogan’s belt would be like comparing ice cream to horse manure.”

The WWF Run and the “Real” World Champion

Flair’s arrival in the WWF in 1991 was a validation of his career. Vince McMahon treated him with a respect he hadn’t felt in years. “I don’t give contracts,” McMahon told him, “but I’ll shake your hand and tell you that you’ll make the same with me, or more.” Flair won the WWF Championship at the 1992 Royal Rumble in a performance widely considered the greatest in the event’s history. Entering at number three, he lasted nearly an hour to win the title. “I want to jump, I want to party,” Flair told Gene Okerlund after the match. “For the Hulk Hogans and the Macho Mans and the Pipers and the Sids, now it’s Ric Flair, and you all pay homage to the man! Wooooo!”

However, the “dream match” between Flair and Hulk Hogan at WrestleMania VIII never happened. The chemistry wasn’t there on the house show circuit, and office politics intervened. Instead, Flair wrestled Randy Savage. Flair reveals the intense insecurity Savage felt, insisting they script the entire match move-for-move at Savage’s house. “I’d never done anything like this in my life,” Flair admits. “Make no mistake about it—I respect Randy Savage for his skills and accomplishments. But because of his unwillingness to just get in the ring and improvise, I won’t call him a great worker.”

The WCW Nightmare: Bischoff and Russo

Flair returned to WCW in 1993, hoping for a hero’s welcome, but found himself in a political snake pit led by Eric Bischoff. Their relationship was toxic. Flair writes, “No matter what Bischoff claims, he used me to get Hogan and Savage. After that, I was a bit player to him.” Bischoff frequently demeaned Flair in front of the locker room. In one instance, Bischoff mocked Flair’s friend Arn Anderson: “You could roll Arn Anderson in shit and he wouldn’t draw a fly.” Flair writes, “For Bischoff to make a comment like that in front of a group of people was like slapping me in the face.”

The arrival of Vince Russo in WCW only deepened the absurdity. Flair was subjected to humiliating storylines, including being buried alive in the Las Vegas desert and having his head shaved. “Russo was no Vince McMahon,” Flair observes. “The guy wasn’t brilliant; he was obsessed with making himself a star. And he fell in love with two guys who couldn’t draw a dime—Jeff Jarrett and Scott Steiner.”

One of the most degrading moments came when Flair lost a retirement match and was forced to wrestle in a mental institution vignette. “Quite literally, I went from being the WCW World Champion to being a mental patient on television,” Flair laments. “I’m not sure how much of a coincidence it was that this was the same night when Nitro’s eighty-three-week ratings win streak over Raw came to an end.”

Tragedy and Redemption

The book touches on the personal tragedies that have shadowed Flair’s life, particularly the self-destruction of the Von Erich family. Flair recounts wrestling Kerry Von Erich, who was often impaired by drugs. “This is where writing a book like this becomes very personal and very touchy,” Flair writes. “Like most people in wrestling, I was very fond of Kerry. But the simple truth was that he was drug-impaired all the time, whether it was eight in the morning or after midnight.” He describes a match where Kerry showed up with his boots untied and wandered out of the ring to look for a girl in the crowd. “It all became so pathetic that I actually put myself into holds,” Flair admits.

By the time WCW folded in 2001, Flair’s confidence was shattered. He returned to the WWE in 2001, but he felt like a shell of himself. “I went through a period where the Nature Boy wasn’t the Nature Boy,” he confesses. It was his friendship with Triple H (Paul Levesque) that pulled him back from the brink. Triple H refused to let Flair wallow, forming the “Evolution” stable to revitalize Flair’s career.

The emotional climax of the book occurs in Greenville, South Carolina, in 2003, after a match against Triple H for the World Heavyweight Title. Although Flair lost, the locker room emptied to pay him tribute. Shawn Michaels bowed to him on the ramp. “In my life, I only bow down to one person, and that’s Jesus Christ,” Michaels said. “But in my professional life, I wanted Ric to know, he is the man.” Flair wept openly in the ring. “I burst into tears. For so long, it felt like I’d been in a vacuum-sealed chamber with my gloom… Now the glass was shattered, and I could feel everything. And it wasn’t bad anymore. It was great.”

The book concludes with Flair finding peace in his legacy, still performing at a high level in his 50s. He reflects on the toll the business took on his family life, particularly his first marriage to Leslie. “I can’t pinpoint anything that Leslie ever did wrong,” he admits. “I could have been married to Raquel Welch and it wouldn’t have made any difference. I wanted to be Ric Flair, the character the fans saw on television, every minute of every day of my life.”

Review: ★★★★★ (5/5 Stars)

“To Be the Man” is an essential read for any wrestling fan. While Bret Hart’s book is a studious, chronological diary, Flair’s is a stream-of-consciousness party that occasionally crashes into a wall of reality. It captures the manic energy of the 1980s wrestling boom and the chaotic implosion of WCW perfectly. Flair is surprisingly candid about his financial mismanagement (“I’ve paid a million dollars in late penalties and interest to the IRS”) and his insecurities, making the “Nature Boy” human. It is a loud, brash, and emotional ride—much like the man himself.

How to Get the Book

- Physical Copies: The book is out of print in hardcover but widely available in mass-market paperback and trade paperback on Amazon, eBay, and ThriftBooks. Used copies can often be found for under $5.00.

- Digital Editions: An e-book version is available for the Amazon Kindle ($9.99-$12.99) and on Apple Books.

- Audiobook: Unlike Hart’s book, there is no unabridged audiobook read by Flair himself widely available on major platforms like Audible as of 2024, though abridged versions or fan readings may exist on YouTube or trading sites.

- Collector’s Items: Signed copies of the original hardcover release appear on eBay, typically ranging from $50 to $150 depending on the condition and authentication.