In 1986, the Universal Wrestling Federation (UWF) was arguably the most exciting, coherent, and physically intense wrestling product in North America. Born from the ashes of Bill Watts’ Mid-South Wrestling, the UWF was a gritty, episodic powerhouse that featured a roster of legitimate tough guys and future legends like Sting, The Ultimate Warrior, and The Steiner Brothers. It was the only territory that seemed capable of withstanding the national expansion of Vince McMahon’s World Wrestling Federation (WWF).

The Cowboy and the Oil Crunch

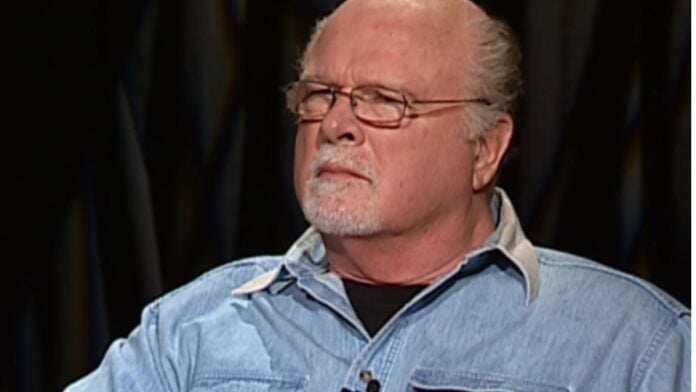

To understand the sale, one must understand the seller. Bill Watts was a massive, intimidating cowboy who booked wrestling like a sport. His television show was episodic, logical, and violent. He created stars by putting them through a grinder of physicality.

In 1986, Watts attempted to take his territory national. He rebranded Mid-South as the UWF and began syndicating his television show across the United States. He was competing directly with the WWF and JCP. The product was hot, the crowds were large, and the talent roster was arguably the best in the world.

However, Watts faced an opponent he could not book against: the economy. The UWF’s core towns were in Oklahoma, Louisiana, and Texas. In the mid-80s, the price of oil collapsed. The regional economy tanked. The blue-collar fans who bought tickets were suddenly unemployed.

Simultaneously, the cost of national expansion was bleeding Watts dry. He was paying for TV time in markets that weren’t generating enough house show revenue to cover the costs. Facing bankruptcy, Watts looked for a buyer. He found Jim Crockett Jr.

The Purchase: April 1987

Jim Crockett Jr. was in the midst of his own war with Vince McMahon. He saw the UWF as a strategic asset. By buying Watts’ territory, he acquired a massive television syndication network, a tape library, and a roster of young, inexpensive talent.

The sale price was reportedly around $4 million, though structured in payments that Crockett would ultimately struggle to make. When the deal was announced, the wrestling world buzzed with anticipation. The idea of a “Super Card” featuring NWA World Champion Ric Flair vs. UWF World Champion “Dr. Death” Steve Williams was a license to print money.

Initially, the plan was to keep the promotions separate. They would run parallel tours, building to massive inter-promotional pay-per-views. However, once the ink was dry, the philosophy in the Charlotte offices of JCP shifted.

The Invasion That Wasn’t

The head booker for JCP was “The American Dream” Dusty Rhodes. Rhodes was a brilliant performer, but as a booker, he was fiercely protective of his “home team.”

When the UWF talent began appearing on NWA television, they were not presented as equals. They were presented as invaders who were inferior to the NWA stalwarts. The narrative quickly established that the “Major League” was the NWA, and the UWF was the minor league.

This was a catastrophic mistake. The UWF had a loyal, rabid fanbase that viewed their wrestlers as the toughest in the world. By burying the UWF stars, JCP alienated the very audience they had just paid millions of dollars to acquire.

The Great American Bash 1987

The burial became undeniable during the Great American Bash tour in the summer of 1987. The tour featured a series of matches pitting NWA stars against UWF stars.

Historically, in inter-promotional feuds, the wins and losses are traded to maintain the credibility of both sides. In this instance, the NWA dominated completely.

The UWF Television Champion, Eddie Gilbert, was defeated. The Western States Heritage Champion, Barry Windham (NWA), defeated UWF heavyweights. The message was clear: if you are from the UWF, you are going to lose.

The most egregious example involved the UWF World Heavyweight Champion, Big Bubba Rogers (formerly the Big Boss Man). He was defeated by the NWA’s “One Man Gang” via count-out in a title match, a finish that made the champion look weak. Shortly thereafter, the title was put on “Dr. Death” Steve Williams, a legitimate tough guy who could have carried the brand. However, even Williams was booked as secondary to the NWA main eventers like Flair, Rhodes, and Luger.

The Unification and the Erasure

The final nail in the coffin was the unification of the championships. JCP decided to merge the titles, which in wrestling terms meant retiring the UWF belts.

At Starrcade ’87, the UWF World Heavyweight Championship was not even defended on the main card in a meaningful way to close the brand. Instead, the dismantling happened over time on television.

Terry Taylor, a top UWF star, was the last UWF Television Champion. In a match against NWA mainstay Nikita Koloff at Starrcade ’87, Taylor—who was technically sound and over with the audience—lost to Koloff in under 20 minutes. The title was unified into the NWA TV title, and the UWF lineage effectively ceased.

The UWF Tag Team Titles were similarly absorbed. The NWA World Tag Team Champions (The Midnight Express) defeated the UWF Tag Team Champions (The Fantastics).

By early 1988, the UWF was gone. The television time slots that Crockett had purchased were converted into NWA programming. The unique, gritty presentation of the UWF—the camerawork, the ringside announcers (Jim Ross), and the pacing—was replaced by the polished, studio-based JCP style.

The Talent Drain

While the brand was destroyed, the talent raid changed the course of wrestling history. Jim Crockett may have killed the name, but he inadvertently acquired the future of the business.

Sting: A young, face-painted bodybuilder in the UWF, Sting was brought into the NWA and immediately put in a match with Ric Flair. The Clash of the Champions I match made Sting a superstar overnight.

The Steiner Brothers: Rick Steiner was a standout in the UWF. He flourished in the NWA, eventually bringing in his brother Scott to form the greatest tag team of the 90s.

Jim Ross: Perhaps the most valuable asset was the announcer. Jim Ross was the voice of the UWF. When he moved to the NWA (and later WCW), he became the voice of a generation.

However, many other talents were lost in the shuffle. Wrestlers like Chris Adams and Iceman King Parsons, who were massive stars in Dallas and New Orleans, found themselves jobbing on the undercard or released entirely.

The Financial Backfire

The tragedy of the UWF purchase is that it did not help Jim Crockett Promotions. In fact, it accelerated JCP’s demise.

The cost of the purchase, combined with the ballooning salaries of the NWA roster and the expense of private jets and limousines, put JCP in massive debt. Furthermore, by alienating the UWF fanbase in the southwest, attendance in those towns plummeted. The fans in Tulsa and Oklahoma City didn’t want to see Dusty Rhodes beat their local heroes; they stopped buying tickets.

Crockett had bought a loyal customer base and immediately drove them away. Just over a year after buying the UWF, Jim Crockett was forced to sell his entire company to Ted Turner in November 1988.

Legacy of the Assassination

The death of the UWF is often cited by historians like Dave Meltzer and Jim Cornette as a prime example of ego destroying profit. If JCP had kept the UWF as a separate brand—similar to the initial Raw vs. SmackDown split—they could have run two profitable tours and created a “Super Bowl” atmosphere once a year.

Instead, they chose to prove a point. They proved that the NWA was “better,” but in doing so, they destroyed the value of the asset they had just purchased.

Bill Watts eventually returned to the wrestling business in 1992 to run WCW, but the magic of the Mid-South/UWF era was gone. The assassination of the UWF remains a cautionary tale about corporate mergers in wrestling: when you buy the competition just to bury them, you usually end up burying yourself.