In the digital age, wrestling news is instantaneous. Twitter, Reddit, and specialized news sites provide real-time updates on injuries, contract signings, and backstage drama for free. However, in the early 1990s, before the internet was ubiquitous, information was a scarce commodity. There was a velvet rope between the fans and the locker room, and for nearly a decade, the only man with the key to that rope was “Mean” Gene Okerlund.

“I can’t talk about it on television. But I can tell you this: a major star has just walked out. If you want the full story, you’ve got to call the WCW Hotline! 1-900-909-9900! Kids, get your parents’ permission!”

It was the ultimate sales pitch. And it worked. The WCW Hotline was not just a side project; it was a financial juggernaut that generated millions of dollars in revenue, funded exorbitant contracts, and arguably invented the modern “dirt sheet” culture by monetizing the fans’ desire for insider knowledge.

The Economics of the 900 Number

To understand the success of the hotline, one must understand the telecommunications landscape of the 1990s. Premium-rate telephone numbers (1-900 numbers) were a booming industry. They were used for everything from psychic readings to dating services to tech support. The business model was simple: the caller was charged a high per-minute fee, which appeared on their monthly phone bill. The revenue was then split between the phone carrier and the content provider.

The WCW Hotline typically charged $1.59 to $1.99 per minute. While two dollars sounds negligible, the strategy was based on volume and duration. The goal was to keep the caller on the line for as long as possible.

A typical call would start with a pre-recorded introduction, often by Okerlund himself. He would welcome the caller, tease the stories coming up, and navigate through a menu of options. “Press 1 for results, Press 2 for rumors…” By the time the caller actually reached the “scoop” they had called for, three or four minutes might have elapsed.

If 100,000 fans called the hotline after a major angle on Nitro and stayed on the line for five minutes, the revenue generated in a single hour could exceed half a million dollars. It was a license to print money, requiring zero physical inventory and minimal overhead.

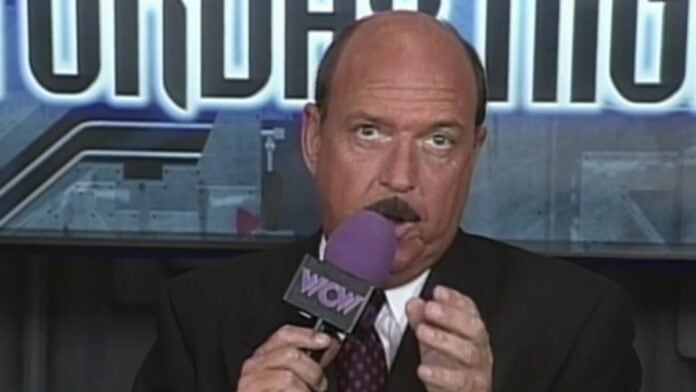

Gene Okerlund: The King of the Pitch

The voice and face of the operation was Gene Okerlund. Already a legend from his time in the American Wrestling Association (AWA) and the World Wrestling Federation (WWF), Okerlund jumped ship to WCW in 1993.

While his on-screen role as an interviewer was vital, his contract was structured heavily around the hotline. In various shoot interviews and podcasts, Eric Bischoff (former WCW President) has confirmed that Okerlund received a percentage of the hotline revenue.

This incentive structure made Okerlund the greatest salesman in the history of the company. He knew that the more vague, urgent, and scandalous his television pitch was, the more money he would make personally. He mastered the art of the “tease.”

- “The boys are walking out!”

- “A former World Champion is in the building!”

- “You won’t believe who was found in the hotel lobby!”

Okerlund delivered these lines with such conviction that fans felt they had to call. He sold the sizzle, even if the steak was often overcooked or nonexistent. In a 2015 interview with Sports Illustrated, Okerlund admitted that the hotline was “the greatest gig I ever had,” acknowledging the massive financial windfall it provided him during the Monday Night Wars.

The Content: Fact vs. Fiction

The content on the hotline was a mix of legitimate news, exaggerated rumors, and complete fabrication. This was the era of the “dirt sheets” (newsletters like the Wrestling Observer), but those had a limited subscriber base. The hotline brought “insider” terms and rumors to the casual television audience.

Sometimes, the scoops were real. The hotline was often the first place to confirm signings. When Hulk Hogan, Randy Savage, or Roddy Piper were negotiating with WCW, the hotline would drop heavy hints.

However, the pressure to generate calls every single week led to “creative” reporting. A tease about a “World Champion being fired” might turn out to be a story about a former NWA champion from the 1970s being let go from a front-office job. A “walkout” might refer to a wrestler leaving the arena early to catch a flight, not quitting the company.

The most infamous example of the hotline’s deceptive nature involved the teasing of WWF defectors. Okerlund would often say, “A major WWF superstar is jumping ship!” Fans would pay the $1.99/minute, waiting to hear if it was Bret Hart or Shawn Michaels, only to find out it was a mid-carder or a referee.

The Brian Pillman Worked Shoot

One of the most sophisticated uses of the hotline occurred during the Brian Pillman “Loose Cannon” saga in 1996. Pillman was booking his own “firing” from WCW to create a buzz. Part of the strategy was to use the hotline to sell the legitimacy of his erratic behavior.

After Pillman broke character on television—telling Kevin Sullivan “I respect you, booker man”—Okerlund went on the hotline to “shoot” with the fans. He claimed that Pillman had gone off-script, that management was furious, and that lawsuits were pending.

Because the hotline was perceived as the place where the “real” news lived, fans believed Okerlund. They paid to hear the updates on Pillman’s contract status. WCW effectively monetized a storyline by pretending it wasn’t a storyline, using the hotline as the medium for the “truth.” This blurred the lines of reality and generated significant revenue while building Pillman’s character.

The Mark Madden Era

As the volume of news increased, Okerlund could not handle all the recordings himself. WCW brought in Mark Madden, a sports talk radio host from Pittsburgh with a sharp tongue and a deep knowledge of the business.

Madden revolutionized the hotline content. While Okerlund was the pitchman, Madden became the voice of the “smart mark.” He openly discussed backstage politics, buried wrestlers he didn’t like, and broke legitimate stories.

Madden famously broke the news that Rick Rude was at a Nitro taping while simultaneously appearing on a taped episode of Raw (with a beard on one show and clean-shaven on the other). This revelation embarrassed the WWF and proved that Nitro was live.

However, Madden’s style also courted controversy. He was less filtered than Okerlund. He would often speculate wildly or offer scathing critiques of the booking, essentially biting the hand that fed him. But because the hotline was generating so much cash, management largely left him alone.

The Dark Side: Tragedy for Profit

The profit-driven nature of the hotline had a grim underbelly. In the wrestling business, tragedy generates interest. When a wrestler died, was arrested, or suffered a catastrophic injury, call volumes spiked.

Critics have pointed out that WCW often exploited these moments. When Brian Pillman died in 1997, or when Louie Spicolli passed away in 1998, the hotline was the primary source of information. Okerlund would appear on TV with a somber face, teasing “tragic news” that required a phone call to hear.

To many, this felt predatory. Charging grieving fans money to hear the details of a favorite wrestler’s death was viewed as a moral low point, even for the carnival world of professional wrestling. Yet, from a business perspective, these were often the most lucrative nights for the service.

The Internet and the End of the Line

The death of the WCW Hotline was not caused by a lack of scandals, but by technology. By the late 1990s, the internet was becoming a household utility. Websites like 1Wrestling.com and WrestlingObserver.com began posting the same news that was on the hotline, but for free (or for a flat monthly subscription).

Why pay $2.00 a minute to hear Mark Madden read a report when you could read it yourself on a dial-up connection?

The “scoops” began to lose their value. The audience became savvier. They realized that Okerlund’s teases were often hyperbolic bait. The call volumes dropped precipitously as the Monday Night Wars wound down.

When Vince McMahon purchased WCW in 2001, the hotline was shut down. The infrastructure was dismantled. The era of the 900 number was over.

Historical Significance

The WCW Hotline is often remembered as a quirky artifact of the 90s, but its impact on the business was profound. It was one of the first successful attempts to monetize the relationship between fans and the backstage reality of the sport.

It funded the company during lean years. Eric Bischoff has stated that in the early 90s, before Nitro became a ratings giant, the hotline revenue was one of the few things keeping the balance sheet healthy. It helped pay for the contracts of stars who would eventually turn the tide of the war.

Moreover, it trained the audience to look behind the curtain. It normalized the consumption of “backstage news” as a companion to the on-screen product. Today’s landscape of wrestling podcasts, Patreon subscriptions, and dirt sheet websites owes its existence to the model perfected by Mean Gene.

Every time a wrestling fan clicks on a “clickbait” headline promising a “major update” on a star’s contract status, they are participating in a digital evolution of the same hustle that started with a 1-900 number and a promise from a man in a tuxedo that he had a secret to tell—for a price.